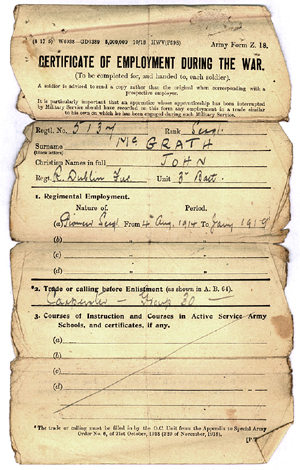

A soldier’s Certificate of Employment during the Great War.

As with their English counterparts, Irishmen enlisted for many different reasons. Some joined up for the wage, many others felt a sense of duty or moral obligation and some naively thought it would be an exciting adventure.

Conscription, though threatened, was never actually introduced in Ireland.

‘C’ Company, 2nd Battalion RDF.

Generally, army regiments were organized on a geographical basis, but many Irishmen joined non-Irish units and the Irish regiments contained men from Scotland, England and Wales. It is therefore difficult to estimate exactly how many Irish people served and died in the Great War. A feature of Great War was the formation of ‘Pals’ battalions, drawn from sports clubs, schools, universities and other community groups.

As the war progressed, heavy losses meant that some regiments were merged. After the war, many regiments were disbanded. Ulster and Southern Irish regiments fought side by side and high regard for the courage demonstrated was mutual. Poet and Nationalist M.P., Tom Kettle, wrote to his wife that if he survived, he would devote himself to the reconciliation of Ulster with Ireland, having witnessed the comraderie of these brothers-in-arms.

“If this war has taught us anything, it is that great things can be done only in a great way.” – Tom Kettle, Political Testament, 1916.

Structures

Before the outbreak of war, there were 20,000 Irish soldiers in the regular British army. Another 30,000 were reservists. Recruits were aged between 19 and 45 years and veterans and reservists up to 45 years could join up. In September 1914, Dublin had three recruitment centres and 58,000 men were mobilized, including 12,000 members of the Special Reserve. Right through the war, the British feared a German invasion either in Britain or Ireland and the Special Reserve had a home defence role.

A Royal Dublin Fusiliers Pin which belonged to a Fusiliers soldier, John McGrath.

Typically, an infantry battalion consisted of 1,000 men. Twelve to fourteen battalions, grouped into 3 brigades made up a division. The British soldiers’ uniform was 1902 service dress: gray collar-less undershirt, a 5-button tunic with closable collar, straight trousers held up by suspenders, leg wraps to be wound from ankle to calf, a trenchcoat, a trenchcap and a leather jerkin for cold weather. Standard issue equipment was a Short Magazine Lee Enfield .303 rifle with a 1907 Wilkinson 17″ blade bayonet. The two ammunition pouches soldiers carried could each hold up to 150 rounds and soldiers could carry an extra 100 rounds. Gas masks were also used and a Mark II pattern steel helmet was introduced in 1916.

Click here to download more about this

Conscription

1st / 8th (Irish) Kings Liverpool Regiment.

This group photograph was taken after a raid 17/18 April, 1918.

Conscription through the Military Services Act, 1916, was not enforced in Ireland. However, by 1918, heavy military losses caused the government to reconsider their position. Irish Parliamentary Party opposition notwithstanding, the Conscription Bill was passed. Under the Bill, conscription could be introduced in Ireland by proclamation. Massive public demonstrations took place both in Belfast and in the South. The government tried enticements such as tying up Home Rule with conscription which caused public confusion. The collapse of the German Spring Offensive dispensed with the immediate need for so many recruits and conscription was not enforced in Ireland. By ignoring the protests of the Irish Party, the government dealt another blow to Redmond’s group and lent weight to Sinn Féin’s argument that attending Westminster was pointless.

Click here to download more about this

Pals Battalions

Groups of workers and sportsmen who enlisted en masse formed Pals battalions. These Pals Battalions were comprised of people from sports clubs, places of employment, past-pupils and staff from schools, graduates, under-graduates and staff at universities. For instance, London stock-brokers became the 10th (Service) Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers.

‘D’ Company, 7th Battalion the Royal Dublin Fusiliers photographed at the Royal (Collins) Barracks, Dublin on the 30th of April, 1915, prior to their departure to Basingstoke, and ultimately Dardanelles.

The Dublin Pals formed ‘D’ Company of the 7th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers and were drawn mainly, but not exclusively, from the city’s professional classes. Addressed at Lansdowne Road by the I.R.F.U. President, Mr. Browning (killed when returning from a route march on Easter Monday 1916, during the Rising), a group of Rugby players volunteered in September 1914.

Many other Dublin Pals had the common bond of attending Trinity College. Some of these refused officer commissions because they wished to be equal with their peers. The then Reid Professor of Criminal Law (a position since held by Irish Presidents, Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese), Ernest Julian, volunteered and died in Gallipoli. This company was nicknamed, ‘The Toffs among the Toughs’. Despite the religious mix of the group, there was no sectarianism.